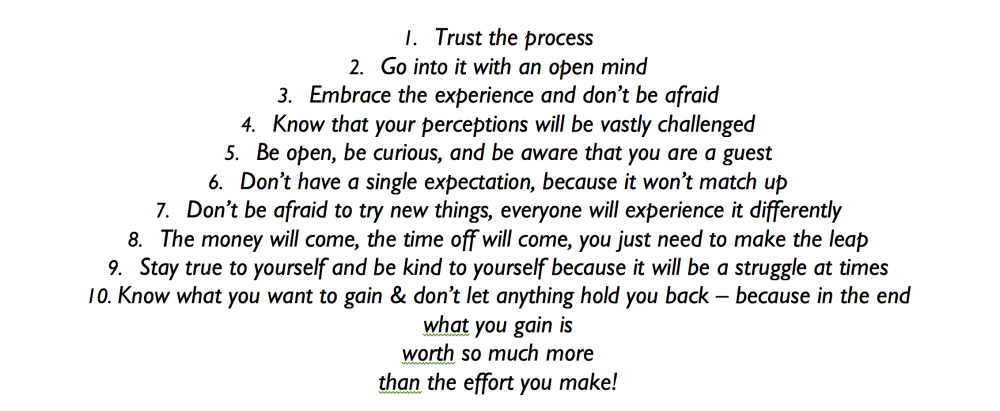

From the previous Field Schoolers, some tips!

MRU students find community in India – By Terry Field, Field School Faciliator

Haridwar India – May 2012

Their voices wake me.

It’s 6 a.m., and the early air is still warm from the day before. The heavy curtain sways very slightly in a light morning breeze. Outside the window of my monk-like room at a rural Indian ashram, the orange glow of dawn is being pulled like a ribbon across the hilly ridge to the East. A few metres away, a group of toddlers, children and teenagers are gathered in the prayer room. Even though they have just woken, and must be a little sleepy-eyed, they squeak, squeal and laugh as they find a space on the room’s floor. A few minutes more at the direction of their adult caregivers they begin to chant a prayer, which is followed by a few minutes of quiet reflection. One of the children is charged each day with conducting the service in celebration of Shiva and other Hindu deities. He or she sprinkles holy water from the Ganga, or Ganges River, on the altar and then ignites a small flame, with each action being a form of devotion and purification.

They close with another prayer and within a few seconds the conversation begins again as they tumble into the courtyard, retrieve their personal metal meal tray and cup, and go together to breakfast. Each of them is either orphaned or abandoned, or has been left tearily by families who couldn’t take care of them. The ashram is a safe and loving place for them to grow-up, and it’s a good place to bring 25 Canadian university students for a study-abroad academic program.

Every morning at Sri Ram Ashram, a 20-minute drive from the holy Hindu city of Haridwar, India, begins the same way. Founded in the 1980s by Hindu scholar and renunciate Baba Hari Dass, who is known to all as Baba-ji, the ashram is today home to about 90 people, including the children and youths, their adult caregivers or “mommies,” the ashram’s director, and its nurse. Together they are a family. The children are not adopted out but stay until they are educated and capable of striking out on their own in their early twenties. Even then they routinely come ‘home’ on weekends with their arrivals being important mini-events. They can’t just slip through the gate but are mobbed by their brothers and sisters, each of whom is acknowledged by their older sibling.

The MRU students are readily absorbed into this pattern of attention, and within hours of arriving are seen being pulled about by several small children eager to show them the garden, the barn, the dorms. Eleven-year-old Deepak, who like the other children is fluent in English and Hindi, eagerly names and describes each fruit and seed growing on the grounds. “You can eat that one but not now…wrong season. But, if you eat that one it will make you ill all the time.” Aside from being an expert botanist he loves and understands all manner of machines, and asks detailed questions about Canada. Our students fall in love with his large serious dark eyes in an instant and are heartbroken to hear that he was brought here, as an infant, by an uncle who could not care for him after Deepak’s mother had died.

Each night during our stay the students and professors meet privately for a debrief designed to focus on lessons learned that day about this community of protection, affection and achievement. A student tells Deepak’s story and her classmates sit for sometime in quiet teary contemplation, knowing too that had he not been brought here he might have died. The circumstances of the other children are equally sad.

Kavita was found at about four years old living as a feral child in the woods. Still socially awkward, and physically challenged, she is now 18, and interacts easily with the students. She is enamoured by photography and the students’ high-end cameras. Her photos of her family, the students, and flowers are all perfectly composed. We resolve to collect cameras for the children to use the next time we bring a group.

The ashram’s dorm buildings, large treed yard and surrounding farm fields are a refuge from the world outside, and from a society defined largely by poverty and a deep adherence to social class and caste. Even though the caste system was officially abolished many years ago, in remains in reality a defining feature of Indian society. It would be an exaggeration to say this place is the children’s only hope but only a mild one.

Life in India for most is a constant challenge on all levels and a daily struggle for survival for many. Children suffer greatly living in circumstances where they don’t always eat properly, or don’t attend school beyond a certain age, or need to work to support their families. Girl children are still, and in rural India particularly, considered at times to be financial liabilities on their large families.

Our students’ study-abroad academic program offers lessons no Canadian classroom can effectively impart. It is one thing to consider community development as a concept but quite another to see it yourself, and especially when life inside the ashram stands in such stark contrast to the world outside its walls. As you’d expect, university professors don’t come into work one day with a brilliant idea to shuttle students out of the country. There are many steps to take and hurdles to clear, and over many months, before the MRU group A arrives in New Delhi on a humid May evening in 2012.

Over a year earlier, my colleague at Mount Royal University, in Calgary, and I first talked about Sri Ram Ashram and its unique approach to taking care of children who might otherwise receive no care at all. The ashram’s director, Rashmi Cole, had for some years been involved with Crossfit, an organization that promotes fitness through a series of owner-operated gyms including a couple in Calgary. The Crossfit method makes use of low tech tools such as medicine balls, jump ropes and free weights to mimic the kinds of movement a person might normally make in a day: lifting, bending, pulling on things, pushing other things around. The focus on low cost equipment appealed to an under resourced children’s home manager in India who among the group had a number of adolescent males who needed something physical to do as part of their daily routine.

Crossfit Calgary decided to raise some money and donate a piece of equipment to the ashram, and Mount Royal social work professor Yasmin Dean was among the organizers of the effort. It was clearly a great cause, and her enthusiasm for the project was infectious. She and some other Crossfit members were already planning to take the donated gear to India when she floated the idea of taking some Mount Royal students to stay at the ashram at some point as part of their coursework.

Yasmin and I had both been involved in a number of international student exchange and field school projects, and the idea of having students go and participate in some way in ashram life was an idea obviously loaded with potential. She and the others from Crossfit spent a week at the ashram in January 2011 meeting the staff, playing with the toddlers, and holding the babies. “We have to do this, we have to take students,” Yasmin said after returning home.

How ordinary life at the ashram seems on the surface of things. The children do their homework after school, they play in the yard, Bollywood dance together, talk to and tease one another. But how extraordinary it actually is.

Girls and boys each have their own dorm space, and rooms are shared by children of the same or similar age. The children’s rooms are small and each has three or more beds. Their mommies are mostly middle-aged local women who live in, care for and discipline the children.

Our students stay in pairs in a separate building, which is reserved for guests, though the central indoor patio is in almost constant use for dancing practice and various annual special events – from birthdays, to staging plays, to holiday celebrations including Christmas: a decidedly non-Hindu event that is recognized because the ashram has so many North American visitors and supporters, and to promote understanding of other cultures.

Meals at the ashram are large communal affairs. The kitchen area is fenced and gated to keep away the ever-present wild monkeys. The children, staff and guests file into the dining hall together trays, cups and utensils in hand, and find a spot on the floor on either side of long woven mats. Women and girls file to the right, men and boys to the left. After a prayer of thanks, the cook and several of the children move along the rows and ladle meatless food onto the trays: dal, rice, soybeans, greens, roti, milk with a little sugar for the children, yoghurt from their own cows, and chai for all.

There are two shifts, with the younger children and teens first, young adults and staff afterwards. The same time every day, day after day, and the same pattern each day for lunch and supper. The children, who have all been taught English at the ashram-run school, enjoy sitting beside our students. Contrary to the normal rule, the room is full of chatter. When there are no guests around, the room is much quieter. The children arrive on time, say their prayer, eat in silence and get on with their day. But with a group of Canadian students and professors in the house, the children have trouble containing their enthusiasm.

The ashram encourages visitors including larger groups such as ours. Everyone who stays is invited into the daily life and can interact with the children if they choose to do so. The fees collected from guests help maintain the place, but the guests also help bring the world outside India to the children. During our stay the school is closed for a week for a local holiday and the students work in shifts with the children on school projects. The younger ones search online for information and images on animals and geography, while the older ones look at social issues. The computer room, like the rest of the place, is buzzing with life. Our students, too, have projects to complete including photo essays, videos and painting a partnership mural on the whitewashed walls of the swimming pool.

The week passes quickly with the daily work by all, playing cricket and basketball in the yard, relaxing with chai after the post-lunch rest period, meals, daily prayer and special events such as the wind-up dinner and dance party for our group.

Starting mid-afternoon of our last full day before catching the train to Delhi and flights home, the older children start preparing the outdoor patio for the party. They string wires in the trees and to the sides of the buildings, and set up lights and speakers connected to the sound system. Yasmin and the director, Rashmi, head to Haridwar to get cake and ice cream for all. Our students rehearse their Bollywood dance number one last time just hours before they will don Sarees and other traditional costumes, and take the ‘stage’ for the party’s grand finale. Dinner will happen afterwards and outside in the barely cooled darkness of a near 40 degree day.

The party begins with some dances by the children: younger ones first, then the older ones, and finally the young adults. They are excellent dancers and enjoy doing it. The dancers become spectators in turn, and cheer on every move and swirl their siblings make. MRU’s turn arrives. Yasmin and I and the students go Bollywood and put our week of practice, overseen and choreographed by one of the ashram’s older residents, 23-year-old Prema, who takes her dancing very seriously. It is easy to forget, and difficult when you remember, that police brought her to the ashram at 10-years-old. She had been left in the market in Haridwar by her mother, who had promised to come back for her but never did.

We line up, the music starts, and we go through the moves. One of our students is a dancer and we, or at least I, watch her for cues as we move more-or-less together through a four to five minute high tempo tune. It ends with the students in a line and Yasmin and I hidden behind them. Then they move slightly leaving a space for us to walk through and bow to our hosts and new friends, who erupt in applause, laughter and affection.

Dinner follows, and cake and ice cream follows after that. The little ones are sent off to bed, the older ones linger to chat, and our night ends with our usual debrief, which is unusually subdued. The students are quiet, sad and a little overwhelmed when one says: “I thought we were coming over here to help them, and now I feel like they have helped me.” It is a shared sentiment and a reminder to us all that all communities have strengths and potential, and that we as Canadians have as much or more to learn from others as they have to learn from us.