You are about to embark on one of the most significant experiences you will encounter in life. Living and studying abroad and experiencing a culture that may be dramatically different can be a challenging, yet extremely rewarding event for many students. Review the cultural aspects of living abroad before departure so that you are prepared through any adjustment period you may experience.

Concept of Culture

Culture…

- influences our expectations of what is appropriate or inappropriate

- is learned

- reflects the values of a society

- frames our experiences

- provides us with patterns of behavior, thinking, feeling, and interacting

In summary, culture affects every aspect of daily life – how we think and feel, how we learn and teach, or what we consider to be beautiful or ugly. However, most people are unaware of their own culture until they experience another! In fact, we don’t usually think about our culture until somebody violates a culturally-based expectation or we find ourselves in a situation where we have the feeling that WE violated somebody else’s cultural expectations, but are uncertain how.

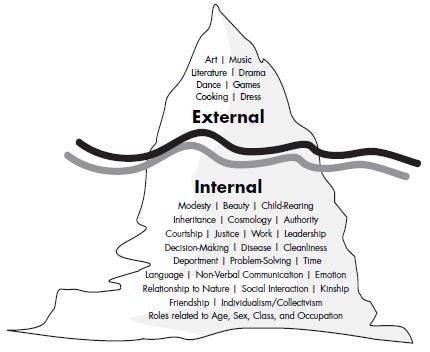

So much of what causes conflict or confusion is the part of the culture that we can’t see or touch. Consider the following illustration and notice the differences between the aspects of culture above and below the “waterline.” The “tip of the iceberg” is the behavior and “external culture” that can be easily observed. The waterline marks the transition into beliefs. And the bottom portion of the iceberg represents the values and thought patterns that make up the “internal culture” which is subconscious and more difficult to observe. Cultural misunderstandings and conflicts arise mostly out of culturally-shaped perceptions and interpretations of each other’s cultural norms, values, and beliefs (those elements below the waterline). Entering another culture is like two icebergs colliding – the real clash occurs beneath the water where values and thought patterns conflict.

THE ICEBERG CONCEPT OF CULTURE

Graphic adapted from Understanding and Coping with Cross Cultural Adjustment Stress

in R.M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the Intercultural Experience, page 160.

CULTURE SHOCK

Culture shock can be defined as “a set of emotional reactions to the loss of perceptual reinforcement from one’s own culture, to new culture stimuli which have little or no meaning, and to the misunderstanding of new and diverse experiences” (Peter Adler). It can also be defined as the expected confrontation with the unfamiliar (R. Michael Paige). However, experts feel that the name “culture shock” is misleading because it makes us think of a single moment of shock rather than the more accurate idea that culture shock evolves over a longer period of time and involves mixed emotions. Although a culture can be shocking at times, the reaction to differences is usually more subtle because it is the accumulation of many experiences in a new culture that forms our opinions. For this reason, many experts in this field prefer the term “culture fatigue.”

Stages of Culture Shock

There are four main stages of culture shock; honeymoon, culture shock, adjustment, and adaptation. The honeymoon stage is full of excitement and great expectations. Everything is new and intriguing. Initially you’ll love the host country, but the feeling won’t last forever. This stage can last from anywhere from a week or two to a few months. All of a sudden, you’ll find yourself wondering why you are stranded miles away from home and everyone around you is acting so strangely. Eventually, you’ll start focusing on the differences between the culture you are familiar with and the new on you’ve found yourself in.

The next phase is the adjustment phase. Now, the worst is over and you’re on your way to feeling better. You are beginning to become more comfortable with the new culture, and you are making more friends and picking up on cultural clues you missed before. However, there are some things you will never get used to. It could be the food, the weather, the lines at the post office, but it’s ok. You are never going to like everything, and you’re learning to deal with it.

Finally, you’ll reach the adaptation phase where you are able to function comfortably and successfully in two cultures. Not everyone will experience a severe case of culture shock or face any of these symptoms. Just don’t be surprised if you do experience some culture shock, it’s very normal. Don’t forget that others are feeling the same way and there are people who can help you get through it. You’ll want to go home, but give it a chance. Chances are you will get over this bump and move on to the next stop of the roller coaster.

Symptoms of Culture Shock:

- Homesickness

- Unexplainable crying/anger/irritability/sensitivity

- Stereotyping

- Excessive sleep

- Compulsive eating or drinking

- Boredom

- Family tension or conflict

- Unusually poor academic performance

- Withdrawal/isolation

- Exaggerated cleanliness/obsession with hygiene

- Hostility towards locals

Survival strategies for Culture Shock

Going abroad requires that you adjust to the same sorts of things that you would if you moved to another part of the United States: being away from family and friends, living in an unfamiliar environment, meeting new people, adjusting to a different climate, and so on. These changes alone could cause high stress levels, but you will also be going through cultural adjustments and you may experience “culture shock.” In another cultural context, you will often find that your everyday “normal” behavior becomes “abnormal.” The unspoken rules of social interaction are different, and the attitudes and behaviors that characterize life in the United States are not necessarily appropriate in the host country. These “rules” concern not only language differences, but also wide-ranging matters such as family structure, faculty-student relationships, friendships, and gender and personal relations.

One way to handle these social and personal changes is to understand the cycle of adjustment that occurs. You can expect to go through an initial period of euphoria and excitement as you are overwhelmed by the thrill of being in a totally new and unusual environment. This initial period is filled with details of getting settled into housing, scheduling classes, meeting new friends, and a tendency to spend a great deal of time with other U.S. students, during both orientation activities and free time.

As this initial sense of “adventure” wears off, you may gradually become aware that your old habits and routine ways of doing things are no longer relevant. A bit of frustration can be expected, and you may find yourself becoming unusually irritable, resentful, and even angry. Minor problems suddenly assume the proportions of major crises, and you may grow somewhat depressed. Your stress and sense of isolation may affect your eating and sleeping habits. You may write letters, send emails, or call home criticizing the new environment and indicating that you are having a terrible time adjusting to the new country. Symptoms include anxiety, sadness, and homesickness.

The human psyche is extremely flexible, however, and most students weather this initial period and make personal and academic adjustments as the months pass. You may begin to spend less time with U.S. Americans and more time forming friendships with local people. You may even forget to communicate home. Finally, when the adjustment is complete, most students begin to feel that they are finally in tune with their surroundings, neither praising nor criticizing the culture but becoming, to some extent, part of it.

Recognizing the existence of and your vulnerability to culture shock will certainly ease some of the strain, but there are also several short-term strategies that you can use beforehand as well as on site when you recognize culture shock and are faced with the challenge of adjustment.

Become more familiar with the local language

Independent study in the local language should facilitate your transition. Continue your study of the foreign language before and throughout your program. Rent and watch foreign films to become accustomed to the rhythm and sounds of the language of your new home. Do not become so concerned with the grammar and technicalities of a language that you are afraid to speak once you are abroad.

Know your own country

You will find that people around the world often know far more about the United States and its policies than you do. Whether or not you are familiar with current events, particularly foreign policy, expect to be asked about your opinions and to hear the opinions of others. Start preparing now by reading newspapers and news magazines.

Examine your motives for going

Although you will certainly do some traveling while you’re abroad, remember that your program is not an extended vacation. Set realistic academic goals, particularly if you are studying in another language. Reduce your expectations or simplify your goals in order to avoid disappointment or disillusionment, but don’t forget to study!

Recognize the value of culture shock

Culture shock is a way of sensitizing you to another culture at a level that goes beyond the intellectual and the rational. Just as an athlete cannot get in shape without going through the uncomfortable conditioning stage, so you cannot fully appreciate the cultural differences that exist without first going through the uncomfortable stages of psychological adjustment.

Expect to feel depressed sometimes

Homesickness is natural, especially if you have never been away from home. Remember that your family and friends would not have encouraged you to go if they did not want you to gain the most from this experience. Don’t let thoughts of home occupy you to the point where you are incapable of enjoying the exciting new culture that surrounds you. Think of all that you will share with your family and friends when you return home.

Expect to feel frustrated and angry at times

You are bound to have communication problems when you are not using your native language or dialect. Even if they speak English in your host country, communication may be difficult! Moreover, people will do things differently in your new home and you will not always think that their way is as good as yours. Once you accept that nothing you do is going to radically change the different cultural practices, you will save yourself from real frustration. Remember that you are the foreigner and a guest in the other culture.

Expect to hear criticism of the United States

If you educate yourself on U.S. politics and foreign policies, you will be more prepared to handle these discussions as they occur. Remember that such criticism of U.S. policies is not personal. Don’t be afraid to argue if you feel so inclined. Most foreign nationals are very interested in the U.S. and will want to know your opinions.

Do not expect local people to come and find you

When was the last time you approached a lonely-looking foreign student with an offer of friendship? Things are not necessarily any different where you are going. If you are not meeting people through your classes, make other efforts to meet them. Take advantage of the university structure and join clubs, participate in sports, attend worship services, participate in volunteer and service-learning projects, and attend other university-sponsored functions. Maintain a sense of meaning in your life and allow time for leisure activities.

- Keep your sense of humor and positive outlook

Almost all returned study abroad students have wonderful stories about how much fun they had during their time abroad. If you have a terrible, frustrating day (or week) abroad, remember that it will pass. Time has a way of helping us remember the good times and turning those horrible times into fascinating stories!

- Write a journal or blog

One of the best ways to deal with cultural adjustments and to reflect thoughtfully on the differences between the U.S. and other cultures is to regularly write in a journal. As you write, you’ll think your way out of the negative reactions that may result from your unfamiliarity with language and cultural behavior. Journaling will force you to make meaningful comparisons between your own culture and that of the host country. When you return home, you’ll have more than just memories, souvenirs, and photos of your time abroad; you’ll have a written record of your changing attitudes and the process of learning about the foreign culture.

- Adopt coping strategies that work for you

Keep in touch with friends and family, but not to the point where you are so consumed with calling and emailing that you miss out on the study abroad experience. Exercising can also contribute to improved mood and better sleep.

Talk to someone if you have a serious problem

The resident director, program leader, or an USD staff member is near at hand to counsel students with serious problems. He/she has firsthand experience with making adjustments abroad and can be a real friend in times of need. Share smaller problems with other students, since they are going through the same process and can provide a day-to-day support group.

Adjusting to a New Culture

Studying abroad is an invaluable experience – a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to live in a foreign country, learn its customs and culture, and adapt to new surroundings. The success of your experience depends upon your own efforts to acclimate yourself to living and studying in a foreign culture. You will have moments of exhilaration and moments of real frustration. Gradually, as you come to terms with the culture, the frustrations will become fewer and fewer.One of the greatest benefits of living in a foreign country is an added depth of appreciation and understanding of U.S. culture. The insights you will gain into yourself and your native culture will be of immeasurable value. As you adjust to your study abroad environment, you will have to deal with real as well as perceived cultural differences. Keep in mind that people of other cultures are just as adept at stereotyping the U.S. American as we are at stereotyping them – and the results are not always complimentary.

The following, for example, are a few of the qualities (some positive, some negative) that others frequently associate with the “typical” U.S. American:

- Outgoing and friendly

- Informal

- Loud, rude, boastful

- Hardworking

- Extravagant and wasteful

- Ignorant of other countries

- Wealthy

- Generous

- Always in a hurry

- Promiscuous

- Politically naive

While a stereotype might have some grain of truth, it is obvious when we consider individual differences that not every U.S. American fits this description. Keep in mind that this same thing is true about your hosts vis-à-vis your own preconceptions. Remember that you are an ambassador USD and the United States. Avoid falling into any of the “ugly American” categories.

Post your comment on this topic.